I became fascinated by Bonnard’s “Terrace at Vernonnet” as a student in The Visual Arts and the Opposites, a course taught under the auspices of the Aesthetic Realism Foundation in the museums and galleries of New York City. My meeting with the Bonnard took place in a class at the Metropolitan Museum that the teacher, Marcia Rackow, called “Color on the Move."

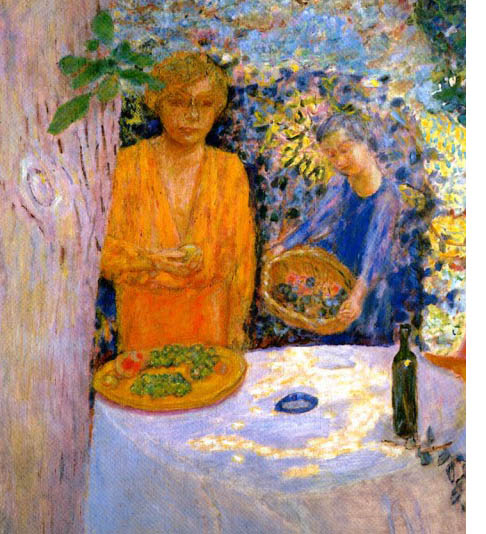

Since then, I’ve come many times to linger in front of the Bonnard, and when I do, I’ve noticed that other people like to visit it too! Color is what I see first — shimmering blues, greens, and violets, and hot tones of orange. Then, I find myself drawn again to the mysterious figure of the woman with the deep meditative expression and the fruit in her hand. Why, I have wondered, has Bonnard made her figure so bright? Is he criticizing the tendency in a person to be aloof, separate, unaffected by things?

Since then, I’ve come many times to linger in front of the Bonnard, and when I do, I’ve noticed that other people like to visit it too! Color is what I see first — shimmering blues, greens, and violets, and hot tones of orange. Then, I find myself drawn again to the mysterious figure of the woman with the deep meditative expression and the fruit in her hand. Why, I have wondered, has Bonnard made her figure so bright? Is he criticizing the tendency in a person to be aloof, separate, unaffected by things?

An artist’s purpose in changing things, I have learned, is so different from the purpose we can have as we use our imaginations in everyday life, changing the facts of reality to make a more comfortable world for ourselves.

In Is Beauty the Making One of Opposites? Eli Siegel asked this about the opposites of truth and imagination in art:

Is every painting a mingling of mind justly receptive of what is before it, and of mind freely and honorably showing what it is through what mind meets? and is every painting, therefore, a oneness of what is seen as item and what is seen as possibility, of fact and appearance, the ordinary and the strange? and are objective and subjective made one in a painting?

Bonnard is painting his home on the Seine in Vernonnet, a work he started in 1920

Show More...

Since then, I’ve come many times to linger in front of the Bonnard, and when I do, I’ve noticed that other people like to visit it too! Color is what I see first — shimmering blues, greens, and violets, and hot tones of orange. Then, I find myself drawn again to the mysterious figure of the woman with the deep meditative expression and the fruit in her hand. Why, I have wondered, has Bonnard made her figure so bright? Is he criticizing the tendency in a person to be aloof, separate, unaffected by things?

Since then, I’ve come many times to linger in front of the Bonnard, and when I do, I’ve noticed that other people like to visit it too! Color is what I see first — shimmering blues, greens, and violets, and hot tones of orange. Then, I find myself drawn again to the mysterious figure of the woman with the deep meditative expression and the fruit in her hand. Why, I have wondered, has Bonnard made her figure so bright? Is he criticizing the tendency in a person to be aloof, separate, unaffected by things?An artist’s purpose in changing things, I have learned, is so different from the purpose we can have as we use our imaginations in everyday life, changing the facts of reality to make a more comfortable world for ourselves.

In Is Beauty the Making One of Opposites? Eli Siegel asked this about the opposites of truth and imagination in art:

Is every painting a mingling of mind justly receptive of what is before it, and of mind freely and honorably showing what it is through what mind meets? and is every painting, therefore, a oneness of what is seen as item and what is seen as possibility, of fact and appearance, the ordinary and the strange? and are objective and subjective made one in a painting?

Bonnard is painting his home on the Seine in Vernonnet, a work he started in 1920

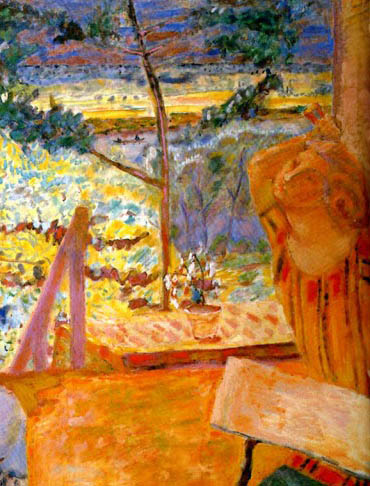

and then did not complete until many years later. The ordinary is present –- his home, familiar cherished objects, and then there is the strange. Times of day mingle. It is dreamlike. How can it be that the sun is shining at once from different parts of the sky?

I have read that Marthe, Bonnard’s wife-companion of many years, is at the center of the painting. And at the edge, oddly, is another woman, though we do not see her right away. It is Renee Monchaty, a woman whom Bonnard loved and wanted to marry earlier in his life. I believe that through the composition of this painting he wanted to show the possibilities of these two important figures in his personal life in relation to the world.

I have read that Marthe, Bonnard’s wife-companion of many years, is at the center of the painting. And at the edge, oddly, is another woman, though we do not see her right away. It is Renee Monchaty, a woman whom Bonnard loved and wanted to marry earlier in his life. I believe that through the composition of this painting he wanted to show the possibilities of these two important figures in his personal life in relation to the world.

The woman representing Marthe has a relation to the sturdy tree in cool purple and a round table, and has the outward serenity of a Greek column. A smaller figure in motion to her right emphasizes her stillness. The woman representing Renee, emerging unexpectedly at the right of the painting, has a relation to a swaying tree, to a bench on the diagonal, and a set of descending steps, and as she swings a tennis racket, she has the outward energy of a ship’s figurehead plowing through the waves. But aren’t the two figures also deeply alike?

The woman representing Renee, emerging unexpectedly at the right of the painting, has a relation to a swaying tree, to a bench on the diagonal, and a set of descending steps, and as she swings a tennis racket, she has the outward energy of a ship’s figurehead plowing through the waves. But aren’t the two figures also deeply alike?

Each is a composition of the diagonal, the vertical, and the circle, and Bonnard relates them through color. He paints them the color of the pavement and the walls, which makes them statuesque, but in a sunny vibrant orange, which gives them life. Meanwhile, through their flatness they are so abstract. They almost seem to be ideas. He is changing them in order to be true to the wide universe that is in each woman.

I love the way Bonnard uses the art imagination, whose purpose is to see things truly. It is so different from the way I once wanted to use imagination for my own comfort and as a refuge from a world which I saw as against me. This began to change from the moment I began to have Aesthetic Realism consultations. My consultants had a beautiful hope for me when they said to me:

“What does Bonnard have to say to you? He wanted to do a painting that does what the eye does. You don’t focus on a detail. You see a color tone. You don’t see the face in the corner until you’ve looked at the whole painting. The eye takes in many things and doesn’t give one thing importance. Bonnard blurs things to show relation. His colors contradict that tragic approach that you have. Do you think Bonnard had disagreements with his wife? He made his wife a part of the composition.”

That is true. I am very grateful to be learning from Aesthetic Realism how to have in my life the composition that art has, that is so present in Bonnard’s great “Terrace at Vernonnet."

I have read that Marthe, Bonnard’s wife-companion of many years, is at the center of the painting. And at the edge, oddly, is another woman, though we do not see her right away. It is Renee Monchaty, a woman whom Bonnard loved and wanted to marry earlier in his life. I believe that through the composition of this painting he wanted to show the possibilities of these two important figures in his personal life in relation to the world.

I have read that Marthe, Bonnard’s wife-companion of many years, is at the center of the painting. And at the edge, oddly, is another woman, though we do not see her right away. It is Renee Monchaty, a woman whom Bonnard loved and wanted to marry earlier in his life. I believe that through the composition of this painting he wanted to show the possibilities of these two important figures in his personal life in relation to the world.The woman representing Marthe has a relation to the sturdy tree in cool purple and a round table, and has the outward serenity of a Greek column. A smaller figure in motion to her right emphasizes her stillness.

The woman representing Renee, emerging unexpectedly at the right of the painting, has a relation to a swaying tree, to a bench on the diagonal, and a set of descending steps, and as she swings a tennis racket, she has the outward energy of a ship’s figurehead plowing through the waves. But aren’t the two figures also deeply alike?

The woman representing Renee, emerging unexpectedly at the right of the painting, has a relation to a swaying tree, to a bench on the diagonal, and a set of descending steps, and as she swings a tennis racket, she has the outward energy of a ship’s figurehead plowing through the waves. But aren’t the two figures also deeply alike?Each is a composition of the diagonal, the vertical, and the circle, and Bonnard relates them through color. He paints them the color of the pavement and the walls, which makes them statuesque, but in a sunny vibrant orange, which gives them life. Meanwhile, through their flatness they are so abstract. They almost seem to be ideas. He is changing them in order to be true to the wide universe that is in each woman.

I love the way Bonnard uses the art imagination, whose purpose is to see things truly. It is so different from the way I once wanted to use imagination for my own comfort and as a refuge from a world which I saw as against me. This began to change from the moment I began to have Aesthetic Realism consultations. My consultants had a beautiful hope for me when they said to me:

“What does Bonnard have to say to you? He wanted to do a painting that does what the eye does. You don’t focus on a detail. You see a color tone. You don’t see the face in the corner until you’ve looked at the whole painting. The eye takes in many things and doesn’t give one thing importance. Bonnard blurs things to show relation. His colors contradict that tragic approach that you have. Do you think Bonnard had disagreements with his wife? He made his wife a part of the composition.”

That is true. I am very grateful to be learning from Aesthetic Realism how to have in my life the composition that art has, that is so present in Bonnard’s great “Terrace at Vernonnet."