The Yanomami of the Amazonian rain forest have been known as “the fierce people”, and we have studied their culture in the Anthropology class as we have tried to understand the causes of violence and war. The Yanomami also had a desire to like the world and find it beautiful, which is the subject of this paper. A portrait of a Yanomami headman, Fusiwe, that shows both sides of a self is the subject of Arnold Perey’s seminar paper, “How much feeling – and what kind - should a man have?” I wanted to look again at the story of Helena Valero, the white woman who married Fusiwe, for further evidence of the desire in the Yanomami for beauty. Her first-person story was taken down by anthropologist Ettore Biocca. You will remember that she had been taken from her parents when she was only twelve and lived with the Yanomami, an Amazonian people, for twenty-four years.

Early in her captivity, Helena Valero witnessed a horrific attack on her compound in which many children died, but she did not use it as an excuse for going away from the world in her mind.

Show More...

In a study of cultural evolution by anthropologists Allen Johnson and Timothy Earle (Stanford University Press, 2nd ed., 2000), Helena Valero’s account is respected and used as source material. The authors present evidence that the resources the Yanomami depended on were being depleted, producing an atmosphere of threat, and keeping old warlike attitudes from changing. These “old attitudes”, we know, represent the great enemy, contempt, which ultimately tore apart the fragile alliances that kin groups were able to form for defense and mutual aid.

anthropologists Allen Johnson and Timothy Earle (Stanford University Press, 2nd ed., 2000), Helena Valero’s account is respected and used as source material. The authors present evidence that the resources the Yanomami depended on were being depleted, producing an atmosphere of threat, and keeping old warlike attitudes from changing. These “old attitudes”, we know, represent the great enemy, contempt, which ultimately tore apart the fragile alliances that kin groups were able to form for defense and mutual aid.

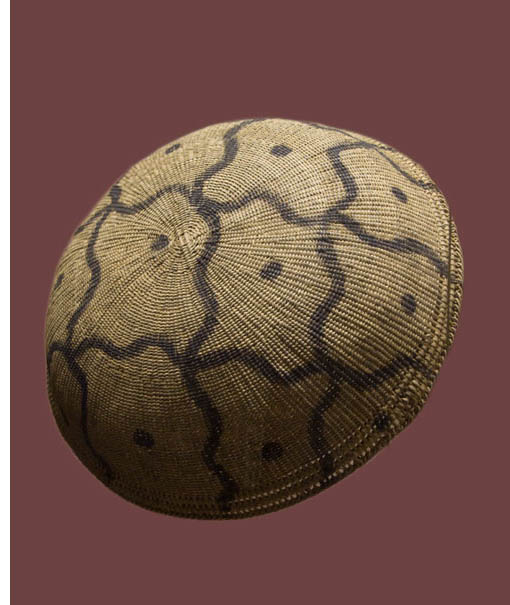

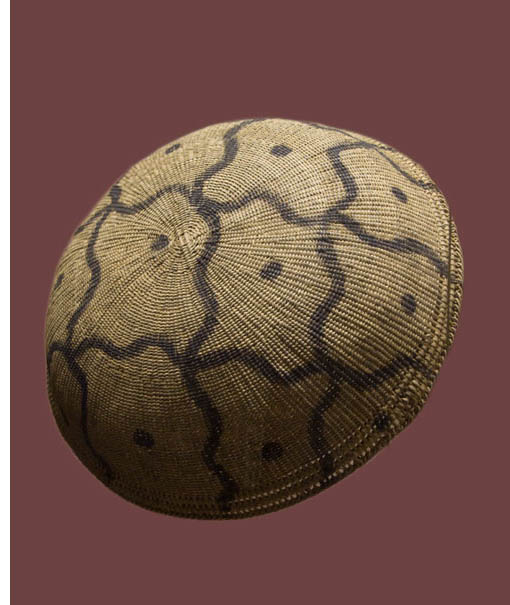

Their desire for affiliation, however, though disappointed, remained, and is expressed in their art. This Yanomami basket has beauty in the way it puts together the tightly constructed and the loosely drawn, wandering lines and tight points, the individual and the collective. I like the fact that the design, which has symmetry, is placed off center. Where the wavy lines cross, there is a feeling of human motion, all of which is confined and made secure by the great circular outer rim. We are moved, because, like Helena Valero and like the Yanomami, these are opposites that we too are trying to put together.

Early in her captivity, Helena Valero witnessed a horrific attack on her compound in which many children died, but she did not use it as an excuse for going away from the world in her mind.

Years later she was able to recall this event in detail for the anthropologist Ettore Biocca. Often in terror of the Yanomami because of the difference they represented and their violent ways, this courageous woman at the same time had a yearning to know the Yanomami and be of them. In “Aesthetic Realism and People” Eli Siegel writes: “No person has ever disliked people and been proud of it. It isn’t because people are people; it is because they are reality. We cannot afford to despise reality.”

Having escaped from the Shamateri, a kin group within the Yanomami, Helena Valero survived by herself in the jungle for seven months. She was not sure she wanted to go on living and deliberately ate some leaves thought to be poisonous. Then, seeing human footprints, and thinking there must be people nearby, she says: “I saw some urucu on the ground, picked it up and painted my whole body red; I scraped the red color with my nails and made colorless stripes across my body. With burnt wood I drew dark lines on my face and my body. I wanted to paint myself like them, so that they should see that I was human like them.” Human – and having beauty. So they found her, and she was taken to live with the Namoeteri, another kin group within the Yanomami.

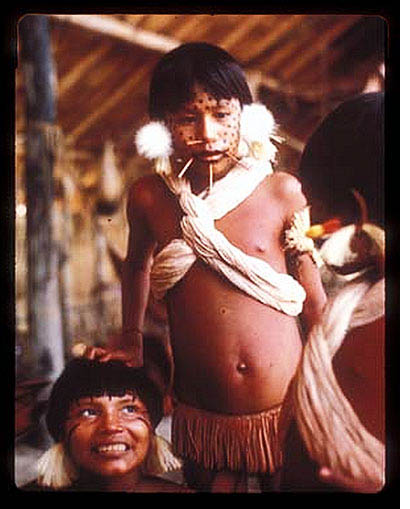

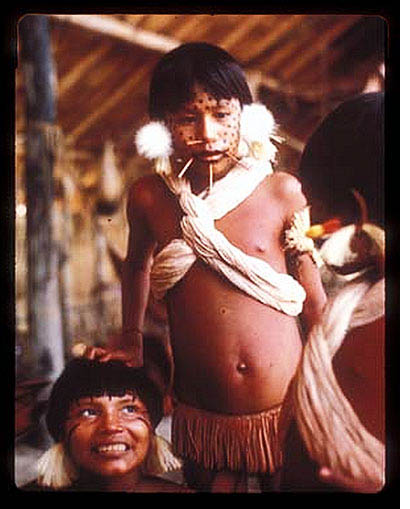

Helena Valero says: “While I was with these people, the time came when I became a woman." She had observed the coming of age ceremony with her previous people, the Shamateri. There is a relation of pleasure and pain that we can see in the photograph of another young woman by Napoleon Chagnon. The young woman must be shut alone for three weeks in a cage made of leaves with a very small entrance. She must lie in a hammock, and is only allowed to come out to rest in a sitting position. She eats and drinks very little, and is forbidden to cry. There is a fire kept for her by her female relatives, which must never become extinguished. At the end of three weeks, the mother brings her outside, builds a fire of banana leaves, and walks her around it. They take her to a rock where she is adorned. Meanwhile she is forbidden to look at men. Her hair is cut, her head is scraped, her body is painted, her ears and her septum are pierced. Strips of twisted cotton to a width of two inches, which must be pure white, are put around her wrist and ankle, below the knee, and around the chest, crossing it behind and below the breasts. The white down of the vulture may be pushed into the openings that have been made in her nose and her ears.

Helena Valero says: “While I was with these people, the time came when I became a woman." She had observed the coming of age ceremony with her previous people, the Shamateri. There is a relation of pleasure and pain that we can see in the photograph of another young woman by Napoleon Chagnon. The young woman must be shut alone for three weeks in a cage made of leaves with a very small entrance. She must lie in a hammock, and is only allowed to come out to rest in a sitting position. She eats and drinks very little, and is forbidden to cry. There is a fire kept for her by her female relatives, which must never become extinguished. At the end of three weeks, the mother brings her outside, builds a fire of banana leaves, and walks her around it. They take her to a rock where she is adorned. Meanwhile she is forbidden to look at men. Her hair is cut, her head is scraped, her body is painted, her ears and her septum are pierced. Strips of twisted cotton to a width of two inches, which must be pure white, are put around her wrist and ankle, below the knee, and around the chest, crossing it behind and below the breasts. The white down of the vulture may be pushed into the openings that have been made in her nose and her ears.

After her seclusion and her adornment had been accomplished, Helena Valero says: “I really looked beautiful.” Soon afterwards, she was taken in marriage by Fusiwe, headman of the Namoeteri.

Helena Valero describes a feast at the Mahekototeri, another kin group of the Yanomami, to whom all the Namoeteri were invited, to share a big banana harvest. There was uncertainty, because such invitations are often the pretext for a fight, but the two-day journey turned out well. They had been invited so that the headman could lay the remains of his father to rest. The men of the Namoeteri, with painted bodies and white falcon’s down on their heads, came in a line and, holding bows and arrows, and performed a dance. Old men recounted tales of fighting in ancient times. The headmen of the two groups spoke, and the Mahekototeri headman said: “Let no one take hallucinogenic drugs." Men went to guard the paths outside the compound in case enemies arrived during the singing. After more dancing, Mahekototeri headman asked the women of the Namoeteri to sing, but most were too shy, so the men sang. People called out “We want Napagnuma, the white woman, to sing” but she was reluctant, so the sister of the headman Fusiwe, taking her arm, sang in her place. Helena Valero says that the voice and song were beautiful, and were repeated many times. Men sang then; their way of singing was different. The singing went until almost midnight, and Napagnuma was asked again and again to sing. Finally, she did sing. There was a song she had heard in her childhood sung by a Brazilian soldier:

It was I, it was I who killed him

It was I, it was I who killed him

The serpent of Baropa

Who killed him was I.

While she sang the others answered in chorus: ‘Opugnuhen, Opugnuhen’, and the old men and women came down from their compound to sit around her. Helena Valero says: “They were happy I was singing.”

Having escaped from the Shamateri, a kin group within the Yanomami, Helena Valero survived by herself in the jungle for seven months. She was not sure she wanted to go on living and deliberately ate some leaves thought to be poisonous. Then, seeing human footprints, and thinking there must be people nearby, she says: “I saw some urucu on the ground, picked it up and painted my whole body red; I scraped the red color with my nails and made colorless stripes across my body. With burnt wood I drew dark lines on my face and my body. I wanted to paint myself like them, so that they should see that I was human like them.” Human – and having beauty. So they found her, and she was taken to live with the Namoeteri, another kin group within the Yanomami.

Helena Valero says: “While I was with these people, the time came when I became a woman." She had observed the coming of age ceremony with her previous people, the Shamateri. There is a relation of pleasure and pain that we can see in the photograph of another young woman by Napoleon Chagnon. The young woman must be shut alone for three weeks in a cage made of leaves with a very small entrance. She must lie in a hammock, and is only allowed to come out to rest in a sitting position. She eats and drinks very little, and is forbidden to cry. There is a fire kept for her by her female relatives, which must never become extinguished. At the end of three weeks, the mother brings her outside, builds a fire of banana leaves, and walks her around it. They take her to a rock where she is adorned. Meanwhile she is forbidden to look at men. Her hair is cut, her head is scraped, her body is painted, her ears and her septum are pierced. Strips of twisted cotton to a width of two inches, which must be pure white, are put around her wrist and ankle, below the knee, and around the chest, crossing it behind and below the breasts. The white down of the vulture may be pushed into the openings that have been made in her nose and her ears.

Helena Valero says: “While I was with these people, the time came when I became a woman." She had observed the coming of age ceremony with her previous people, the Shamateri. There is a relation of pleasure and pain that we can see in the photograph of another young woman by Napoleon Chagnon. The young woman must be shut alone for three weeks in a cage made of leaves with a very small entrance. She must lie in a hammock, and is only allowed to come out to rest in a sitting position. She eats and drinks very little, and is forbidden to cry. There is a fire kept for her by her female relatives, which must never become extinguished. At the end of three weeks, the mother brings her outside, builds a fire of banana leaves, and walks her around it. They take her to a rock where she is adorned. Meanwhile she is forbidden to look at men. Her hair is cut, her head is scraped, her body is painted, her ears and her septum are pierced. Strips of twisted cotton to a width of two inches, which must be pure white, are put around her wrist and ankle, below the knee, and around the chest, crossing it behind and below the breasts. The white down of the vulture may be pushed into the openings that have been made in her nose and her ears. After her seclusion and her adornment had been accomplished, Helena Valero says: “I really looked beautiful.” Soon afterwards, she was taken in marriage by Fusiwe, headman of the Namoeteri.

Helena Valero describes a feast at the Mahekototeri, another kin group of the Yanomami, to whom all the Namoeteri were invited, to share a big banana harvest. There was uncertainty, because such invitations are often the pretext for a fight, but the two-day journey turned out well. They had been invited so that the headman could lay the remains of his father to rest. The men of the Namoeteri, with painted bodies and white falcon’s down on their heads, came in a line and, holding bows and arrows, and performed a dance. Old men recounted tales of fighting in ancient times. The headmen of the two groups spoke, and the Mahekototeri headman said: “Let no one take hallucinogenic drugs." Men went to guard the paths outside the compound in case enemies arrived during the singing. After more dancing, Mahekototeri headman asked the women of the Namoeteri to sing, but most were too shy, so the men sang. People called out “We want Napagnuma, the white woman, to sing” but she was reluctant, so the sister of the headman Fusiwe, taking her arm, sang in her place. Helena Valero says that the voice and song were beautiful, and were repeated many times. Men sang then; their way of singing was different. The singing went until almost midnight, and Napagnuma was asked again and again to sing. Finally, she did sing. There was a song she had heard in her childhood sung by a Brazilian soldier:

It was I, it was I who killed him

It was I, it was I who killed him

The serpent of Baropa

Who killed him was I.

While she sang the others answered in chorus: ‘Opugnuhen, Opugnuhen’, and the old men and women came down from their compound to sit around her. Helena Valero says: “They were happy I was singing.”

In a study of cultural evolution by

anthropologists Allen Johnson and Timothy Earle (Stanford University Press, 2nd ed., 2000), Helena Valero’s account is respected and used as source material. The authors present evidence that the resources the Yanomami depended on were being depleted, producing an atmosphere of threat, and keeping old warlike attitudes from changing. These “old attitudes”, we know, represent the great enemy, contempt, which ultimately tore apart the fragile alliances that kin groups were able to form for defense and mutual aid.

anthropologists Allen Johnson and Timothy Earle (Stanford University Press, 2nd ed., 2000), Helena Valero’s account is respected and used as source material. The authors present evidence that the resources the Yanomami depended on were being depleted, producing an atmosphere of threat, and keeping old warlike attitudes from changing. These “old attitudes”, we know, represent the great enemy, contempt, which ultimately tore apart the fragile alliances that kin groups were able to form for defense and mutual aid. Their desire for affiliation, however, though disappointed, remained, and is expressed in their art. This Yanomami basket has beauty in the way it puts together the tightly constructed and the loosely drawn, wandering lines and tight points, the individual and the collective. I like the fact that the design, which has symmetry, is placed off center. Where the wavy lines cross, there is a feeling of human motion, all of which is confined and made secure by the great circular outer rim. We are moved, because, like Helena Valero and like the Yanomami, these are opposites that we too are trying to put together.