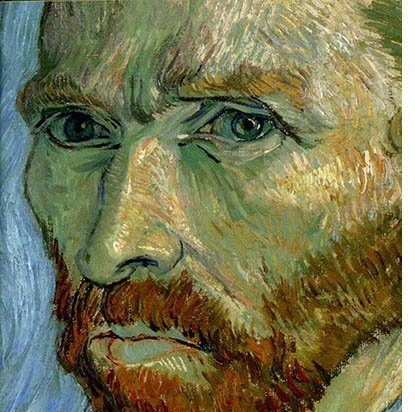

Though I have had big feelings about the work of Vincent Van Gogh since I was a child, when I saw a close up of the tense, troubled gaze in his last self portrait I had a feeling that was new to me.

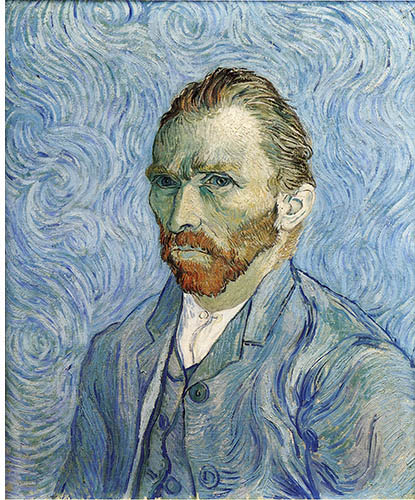

Though I have had big feelings about the work of Vincent Van Gogh since I was a child, when I saw a close up of the tense, troubled gaze in his last self portrait I had a feeling that was new to me.Van Gogh was in the asylum at Saint-Remy when he painted it, in September 1889. He had come there in May. At the beginning of June, when he was able to go into the open air and paint in the surrounding wheat fields, hills, and olive groves, he was greatly inspired and energetic. He was especially affected by the cypresses. In early July, as he sought to represent the view from his bedroom window, he produced one of his greatest works, ’The Starry Night’. In mid-July he suffered an attack of epilepsy, and from then until the end of August, he was unable to paint. After his recovery, he went back to his studio in the asylum and returned to the study of the figure.

He wrote to Theo, his brother: ‘They say — and I am willing to believe it — that it is difficult to know yourself — but it isn’t easy to paint yourself either. So I am working on two

portraits of myself at this moment — for want of another model…. One I began the day I got up; I was thin and pale as a ghost…. But since then I have begun another one, three-quarter length on a light background. ’This one, he later wrote to his sister Wil, ‘has rather the true character, I think.’

portraits of myself at this moment — for want of another model…. One I began the day I got up; I was thin and pale as a ghost…. But since then I have begun another one, three-quarter length on a light background. ’This one, he later wrote to his sister Wil, ‘has rather the true character, I think.’It is an intense and deeply moving work. In Is Beauty the Making One of Opposites? Eli Siegel asked this about outline and color:

DOES every successful example of visual art have a oneness of outward line and interior mass and color? — does the harmony of line and color in a painting show a oneness of arrest and overflow, containing and contained, without and within?

Vincent Van Gogh looks at himself, wanting to relate what he feels inside to what he sees outside, and to affirm his relation to the world on a flat surface. He has written of his fears, and he is trying to see.

We look at the eyes, almost tearful under the horizontal brows and at the way they are set in his face. We feel his emotion and his probing intelligence.

The draftsmanship in this self-portrait is breathtaking. To represent the planes of his face, Van Gogh has applied repeated short strokes of pale and medium orange over a blue ground, using green for the shadow areas, subtly changing their direction, creating rough and smooth textures. He has taken great care with the contours of his right temple and his right cheek (to our left). We feel that the bone is hard and that the skin is soft. There is an outline going between sharpness and blur, thickness and thinness, shading defining the hard brow ridge, softened by the eyebrow. There is the delicate line that defines his pale pink ear, and the broken, blood-red, but sensitive line between his lips.

At this time Vincent was reluctant to leave his studio, but the color in this self portrait says his relation to the great outdoor world that he loved to paint is inescapable. He has made his coat and the background the color of a wintry sky touched with the green of twilight. He seems clothed in a landscape. His beard is the blazing red-orange of the setting sun.

Only two months before, Van Gogh had completed his most visionary work, ‘The Starry Night’. Here, its turbulent shapes fill the background and overflow into his figure, setting the cool blues and blue-greens of his rumpled jacket into motion. Meanwhile, all this color and motion is powerfully contained. As the outline curves, narrows, widens, changes direction, breaks, resumes, it gives weight and monumentality to his form. Most of all it is the head, anchored by a triangle of pure white, that imparts power and permanence to his figure.

How beautifully detailed, careful, accurate this work is, and how abandoned, how imaginative, how free it is. Vincent Van Gogh had written in his letters of his hope that if he could only continue working he could save himself. Looking now at his last self-portrait, I am more grateful than ever to be studying this immortal principle of Aesthetic Realism, “The world, art and self explain each other, each is the aesthetic oneness of opposites.” Through his art, Van Gogh is more alive to us than ever, and we can be more alive ourselves.

The draftsmanship in this self-portrait is breathtaking. To represent the planes of his face, Van Gogh has applied repeated short strokes of pale and medium orange over a blue ground, using green for the shadow areas, subtly changing their direction, creating rough and smooth textures. He has taken great care with the contours of his right temple and his right cheek (to our left). We feel that the bone is hard and that the skin is soft. There is an outline going between sharpness and blur, thickness and thinness, shading defining the hard brow ridge, softened by the eyebrow. There is the delicate line that defines his pale pink ear, and the broken, blood-red, but sensitive line between his lips.

At this time Vincent was reluctant to leave his studio, but the color in this self portrait says his relation to the great outdoor world that he loved to paint is inescapable. He has made his coat and the background the color of a wintry sky touched with the green of twilight. He seems clothed in a landscape. His beard is the blazing red-orange of the setting sun.

Only two months before, Van Gogh had completed his most visionary work, ‘The Starry Night’. Here, its turbulent shapes fill the background and overflow into his figure, setting the cool blues and blue-greens of his rumpled jacket into motion. Meanwhile, all this color and motion is powerfully contained. As the outline curves, narrows, widens, changes direction, breaks, resumes, it gives weight and monumentality to his form. Most of all it is the head, anchored by a triangle of pure white, that imparts power and permanence to his figure.

How beautifully detailed, careful, accurate this work is, and how abandoned, how imaginative, how free it is. Vincent Van Gogh had written in his letters of his hope that if he could only continue working he could save himself. Looking now at his last self-portrait, I am more grateful than ever to be studying this immortal principle of Aesthetic Realism, “The world, art and self explain each other, each is the aesthetic oneness of opposites.” Through his art, Van Gogh is more alive to us than ever, and we can be more alive ourselves.