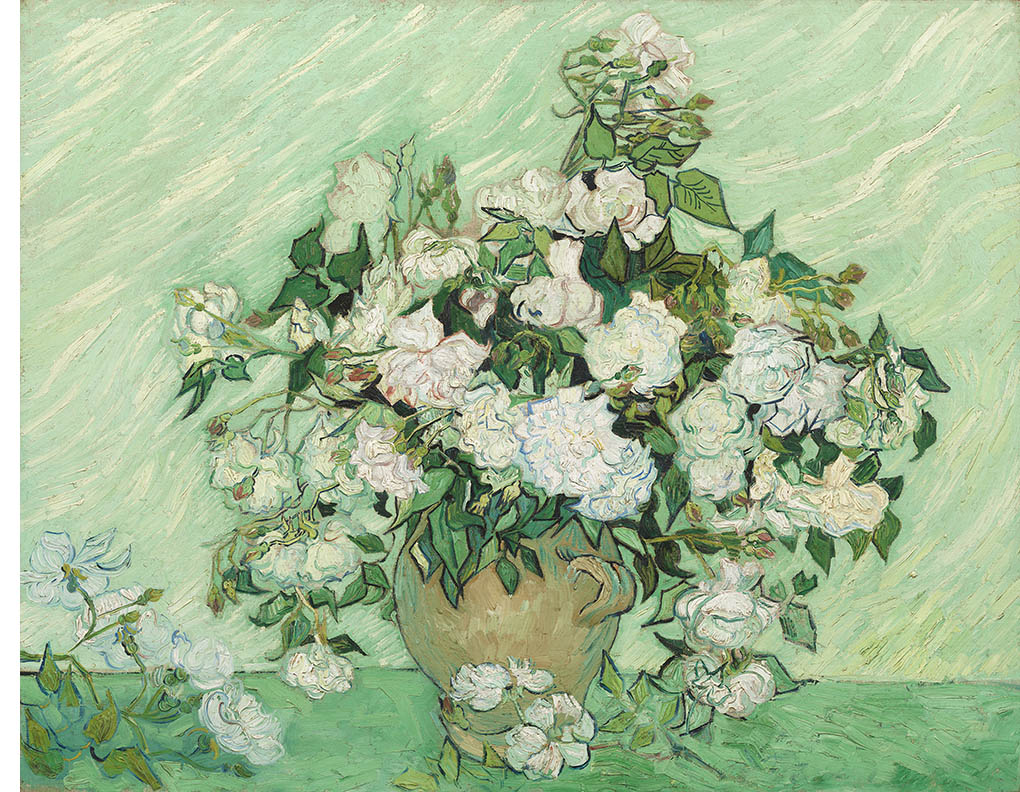

Van Gogh produced four flower canvases in a burst of activity just before he left the asylum in Saint-Remy in May, 1890. This summer New York's Metropolitan Museum brought them together for a special exhibition which closes in one more day. I am so glad I was able to see this wonderful painting face-to-face.

I believe Van Gogh was asking himself about the mysteries of reality as he feverishly painted these roses. They tumble and fall on one another. They turn every which way. There is a regular tempest going on in the painting. Yet he is putting down his brush strokes so confidently, so assuredly.

I believe Van Gogh was asking himself about the mysteries of reality as he feverishly painted these roses. They tumble and fall on one another. They turn every which way. There is a regular tempest going on in the painting. Yet he is putting down his brush strokes so confidently, so assuredly.

In Is Beauty a Making One of Opposites? Eli Siegel asks:

DOES every instance of beauty in nature and beauty as the artist presents it have something unrestricted, unexpected, uncontrolled?—and does this beautiful thing in nature or beautiful thing coming from the artist's mind have, too, something accurate, sensible, logically justifiable, which can be called order?

Van Gogh has painted cabbage roses, which are famous for their fragrance and their massive blooms. Their fragrance spreads and goes out, while the petals are contained and crowd together in the massive flowers. I think this relation of opposites in his subject affected Van Gogh, who wanted to make a composition in his life of freedom and security.

Van Gogh was experimenting with the color in this painting. This is on the side of freedom. He knew there was a chance that the bright pinks might fade – and they have – but it’s hard to imagine how the existing painting could be more beautiful than it already is, with its wonderful textures, created with thick paint, which a soft brush could spread into layers of exquisite delicacy.

Show More...

I believe Van Gogh was asking himself about the mysteries of reality as he feverishly painted these roses. They tumble and fall on one another. They turn every which way. There is a regular tempest going on in the painting. Yet he is putting down his brush strokes so confidently, so assuredly.

I believe Van Gogh was asking himself about the mysteries of reality as he feverishly painted these roses. They tumble and fall on one another. They turn every which way. There is a regular tempest going on in the painting. Yet he is putting down his brush strokes so confidently, so assuredly.In Is Beauty a Making One of Opposites? Eli Siegel asks:

DOES every instance of beauty in nature and beauty as the artist presents it have something unrestricted, unexpected, uncontrolled?—and does this beautiful thing in nature or beautiful thing coming from the artist's mind have, too, something accurate, sensible, logically justifiable, which can be called order?

Van Gogh has painted cabbage roses, which are famous for their fragrance and their massive blooms. Their fragrance spreads and goes out, while the petals are contained and crowd together in the massive flowers. I think this relation of opposites in his subject affected Van Gogh, who wanted to make a composition in his life of freedom and security.

Van Gogh was experimenting with the color in this painting. This is on the side of freedom. He knew there was a chance that the bright pinks might fade – and they have – but it’s hard to imagine how the existing painting could be more beautiful than it already is, with its wonderful textures, created with thick paint, which a soft brush could spread into layers of exquisite delicacy.

We feel the silkiness of the petals and the rough stiffness of the leaves. Van Gogh attends to what lies under the gorgeously blooming surface. He shows the wiry, powerfully straggly stems in their bare angularity. They are gathered forcefully into an earthy ochre vase.

Part of the freedom situation in the painting is the individuality with which Van Gogh has painted every flower, every bud, every leaf. Part of the order situation is Van Gogh’s passion for geometry. The blooms are arranged in diagonal bands within a circle. Look at the way the roses, trailing on their stems, almost complete the circle at the bottom of the canvas. Van Gogh has put most of the flowers to the right, poising them over the edge of the vase, while the motion of the background, flowing softly from upper right to lower left restores the balance.

Adding to the freedom of the composition are two opposing motions, falling and rising. They correspond to the moods in Van Gogh’s letters and our own inner states. In the left corner is a cluster of roses which has worked its way free. The top blossom does not seem quite there or sure of itself, going off into the air at the top, as the rest of the cluster tumbles forward to rest securely on the ground, all within the strong orderly shape of a right triangle.

Meanwhile, almost touching the top of the canvas, is one exuberant spray with a single rose and multiple buds insistently pointing it against the flow as if it is yearning to go places, do things, see more.

At the time he painted this, in 1890, at the height of his powers, Van Gogh had only three more months to live, but every stroke in this painting is on the side of life. It was the brushwork that drew me to this painting, and my hope to be a more sincere person. I felt that Van Gogh wanted to represent the full reality of each flower, just as in his portraits he wanted to represent the full reality of a person. I am grateful for Van Gogh’s existence, and for Aesthetic Realism, the mighty education based on the principle: “All beauty is a making one of opposites, and the making one of opposites is what we are going after in ourselves.”

Part of the freedom situation in the painting is the individuality with which Van Gogh has painted every flower, every bud, every leaf. Part of the order situation is Van Gogh’s passion for geometry. The blooms are arranged in diagonal bands within a circle. Look at the way the roses, trailing on their stems, almost complete the circle at the bottom of the canvas. Van Gogh has put most of the flowers to the right, poising them over the edge of the vase, while the motion of the background, flowing softly from upper right to lower left restores the balance.

Adding to the freedom of the composition are two opposing motions, falling and rising. They correspond to the moods in Van Gogh’s letters and our own inner states. In the left corner is a cluster of roses which has worked its way free. The top blossom does not seem quite there or sure of itself, going off into the air at the top, as the rest of the cluster tumbles forward to rest securely on the ground, all within the strong orderly shape of a right triangle.

Meanwhile, almost touching the top of the canvas, is one exuberant spray with a single rose and multiple buds insistently pointing it against the flow as if it is yearning to go places, do things, see more.

At the time he painted this, in 1890, at the height of his powers, Van Gogh had only three more months to live, but every stroke in this painting is on the side of life. It was the brushwork that drew me to this painting, and my hope to be a more sincere person. I felt that Van Gogh wanted to represent the full reality of each flower, just as in his portraits he wanted to represent the full reality of a person. I am grateful for Van Gogh’s existence, and for Aesthetic Realism, the mighty education based on the principle: “All beauty is a making one of opposites, and the making one of opposites is what we are going after in ourselves.”