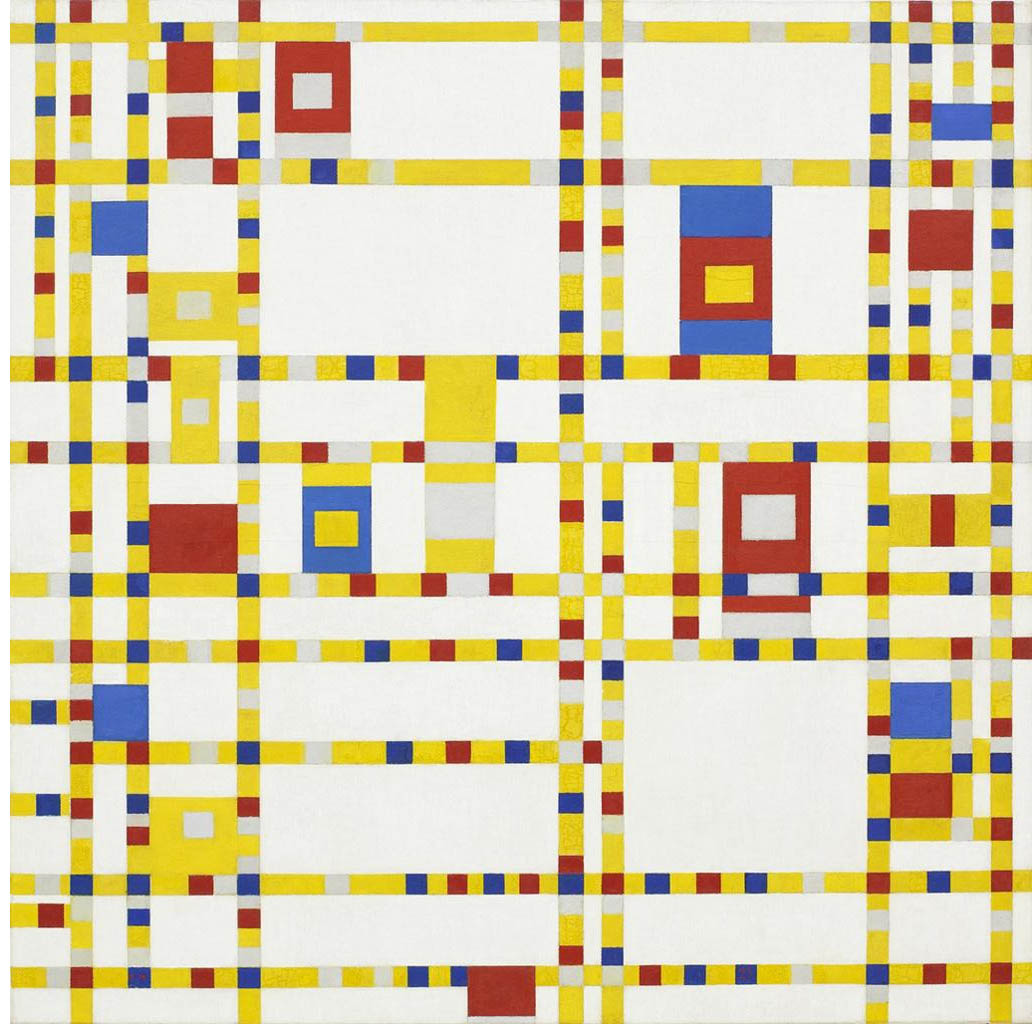

“Broadway Boogie-Woogie” is the culminating work of a great artist, Piet Mondrian. Born in 1872, Mondrian began in the realist tradition of the Dutch masters, became affected by the ideas of theosophy and painting with light, studied in Paris alongside the cubists, and came to his mature style, the color block and the grid, in 1920 when he was 48. In 1942, after the beginning of World War II in Europe, when he came to America, New York City appeared to release something that had been waiting to come forth. Now in his seventies, Mondrian wanted his canvases to dance.

“Broadway Boogie-Woogie” suggests the motion of autos on city streets, of elevators in high rises, of the music pouring out of the clubs on 46th Street. It opposes my desire to be immobile. It does what I want to do.

What I see first in “Broadway Boogie Woogie” is light. Mondrian’s grid has become a brilliant light source in yellow with vibrating square dots of red, gray, and blue. As before, the grid divides space into a series of uneven rectangles. Through two vertical lines near the center of the painting, there is a strong feeling of stability, and on either side there are horizontal and vertical gridlines. The same colors are employed. But there is no true symmetry anywhere, except in the shape of the canvas, which is a perfect square.

Try to find a gridline that repeats itself. Sometimes the gridlines will abruptly break off, sometimes they will continue. Go from dot to dot and discover that each of them is a little off, in no calculated way. Each time we feel a little stir. In Is Beauty the Making One of Opposites, Eli Siegel asks this about the opposites of repose and energy: IS there in painting an effect which arises from the being together of repose and energy in the artist's mind?—can both repose and energy be seen in a painting's line and color, plane and volume, surface and depth, detail and composition?—and is the true effect of a good painting on the spectator one that makes at once for repose and energy, calmness and intensity, serenity and stir?

Show More...

“Broadway Boogie-Woogie” suggests the motion of autos on city streets, of elevators in high rises, of the music pouring out of the clubs on 46th Street. It opposes my desire to be immobile. It does what I want to do.

What I see first in “Broadway Boogie Woogie” is light. Mondrian’s grid has become a brilliant light source in yellow with vibrating square dots of red, gray, and blue. As before, the grid divides space into a series of uneven rectangles. Through two vertical lines near the center of the painting, there is a strong feeling of stability, and on either side there are horizontal and vertical gridlines. The same colors are employed. But there is no true symmetry anywhere, except in the shape of the canvas, which is a perfect square.

Try to find a gridline that repeats itself. Sometimes the gridlines will abruptly break off, sometimes they will continue. Go from dot to dot and discover that each of them is a little off, in no calculated way. Each time we feel a little stir. In Is Beauty the Making One of Opposites, Eli Siegel asks this about the opposites of repose and energy: IS there in painting an effect which arises from the being together of repose and energy in the artist's mind?—can both repose and energy be seen in a painting's line and color, plane and volume, surface and depth, detail and composition?—and is the true effect of a good painting on the spectator one that makes at once for repose and energy, calmness and intensity, serenity and stir?

In Broadway Boogie Woogie there is a relation between matter and space that is dynamic. The sides are dense, with the center more spacious and open. The moving color dots on the grid relate the two. As our eyes travel from one gridline to the next, the colored dots have different effects. The effect is restful at the top, where the dots are gray and spaced out. Look at how different the effect is as we go down the two verticals at the center and different colors lie close together.

Within this central space are witty, vibrant, multicolored blocks, no two alike. The gray and yellow blocks, left, are the most similar. As we go from one to the next, starting at the upper left, going to the center, and then to the lower left, there is a graceful motion. Where the forms are more massive and strikingly different, on the right side of the painting, the effect is more forceful. Mondrian places the most massive of these high in the composition. It touches the gridlines on two sides only, which gives it freedom to move. The red-gray composition is unbounded in a different way, while the blue-yellow-red composition lower right is slowing down. Each block has its own velocity. Toward the edges of the composition are a few simple blocks in red or blue that may have become liberated, or may be seeking to join up with other blocks somewhere else.

What follows is a quote from a class report by Sheldon Kranz in the 1940s, reprinted in The Right of Aesthetic Realism to Be Known 1777: "Dorothy Koppelman read a paper on Piet Mondrian, an abstract painter of great repute, who attempted to get to the meaning of reality in terms of space and time directly, without using representational figures. Mr. Siegel then discussed abstraction in art and how it deals with the philosophic problem of seeing Nothing as Something.

"Art makes the abstract earthy and the earthy abstract. The abstractionist says there is drama within space, in numbers, in the inanimate, as well as in everyday events. The relationship of color and white, rectangle and line, curve and straight line is as dramatic as that of two actors on a stage. Abstraction, Mr. Siegel said, is good when it completes reality and does not get away from it."

I am grateful to be learning about the abstract and the concrete, repose and energy, calmness and intensity, serenity and stir in this Visual Arts class taught by Marcia Rackow. I respect her desire to be fair to the great education that Eli Siegel founded, Aesthetic Realism.

Within this central space are witty, vibrant, multicolored blocks, no two alike. The gray and yellow blocks, left, are the most similar. As we go from one to the next, starting at the upper left, going to the center, and then to the lower left, there is a graceful motion. Where the forms are more massive and strikingly different, on the right side of the painting, the effect is more forceful. Mondrian places the most massive of these high in the composition. It touches the gridlines on two sides only, which gives it freedom to move. The red-gray composition is unbounded in a different way, while the blue-yellow-red composition lower right is slowing down. Each block has its own velocity. Toward the edges of the composition are a few simple blocks in red or blue that may have become liberated, or may be seeking to join up with other blocks somewhere else.

What follows is a quote from a class report by Sheldon Kranz in the 1940s, reprinted in The Right of Aesthetic Realism to Be Known 1777: "Dorothy Koppelman read a paper on Piet Mondrian, an abstract painter of great repute, who attempted to get to the meaning of reality in terms of space and time directly, without using representational figures. Mr. Siegel then discussed abstraction in art and how it deals with the philosophic problem of seeing Nothing as Something.

"Art makes the abstract earthy and the earthy abstract. The abstractionist says there is drama within space, in numbers, in the inanimate, as well as in everyday events. The relationship of color and white, rectangle and line, curve and straight line is as dramatic as that of two actors on a stage. Abstraction, Mr. Siegel said, is good when it completes reality and does not get away from it."

I am grateful to be learning about the abstract and the concrete, repose and energy, calmness and intensity, serenity and stir in this Visual Arts class taught by Marcia Rackow. I respect her desire to be fair to the great education that Eli Siegel founded, Aesthetic Realism.