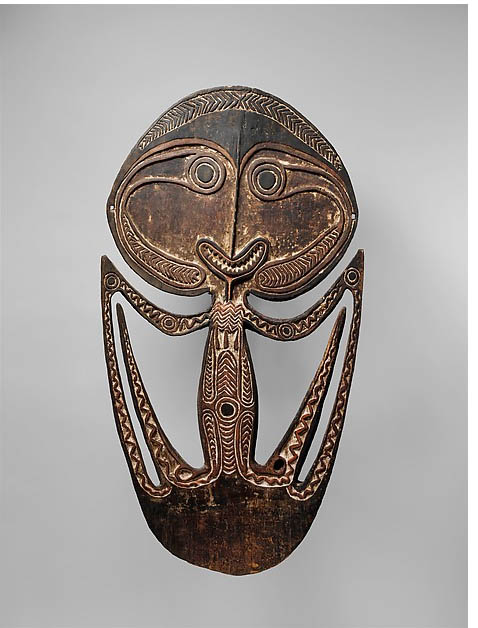

I first saw this smiling agiba in a class at the Metropolitan Museum, in the exhibition “Coaxing the Spirits to Dance." Our text was Eli Siegel's essay, "Art as Humor." Our teachers, Marcia Rackow and Arnold Perey, said that through the opposites we would  be able to look at the unfamiliar and its relation to ourselves and to the world. These were objects from the Papuan Gulf, New Guinea, that the people of this region had associated with divinities living in the rainforest or on the sea, and with ancestral spirits.

be able to look at the unfamiliar and its relation to ourselves and to the world. These were objects from the Papuan Gulf, New Guinea, that the people of this region had associated with divinities living in the rainforest or on the sea, and with ancestral spirits.

Surprisingly, the impressive catalog of the exhibition (2006, Hood Museum, Dartmouth College) made no mention the smiles on so many faces throughout the collection! And there was no suggestion that the people of the Papuan Gulf near Port Moresby have anything in common with ourselves. It reminds me of the unfortunate and oh, so wrong, way I once saw people in Samaná in the Dominican Republic when I first went to live with them, basically as different from myself.

In this lively figure, in its outward form and inner graphic lines, is there containment, but also something that corresponds to our own desire to be free? To be at rest and in motion at once? And to be pleased? In “Art as Humor," Eli Siegel writes that, “Humor in the long run is the seeing of reality as orderly and free, with the free predominating.”

Look at the face of this being. The cheeks are in motion. The brow lines press the eyes and the jawline closer together, while the cheeks swell out, as if impelled by the smile.

Show More...

be able to look at the unfamiliar and its relation to ourselves and to the world. These were objects from the Papuan Gulf, New Guinea, that the people of this region had associated with divinities living in the rainforest or on the sea, and with ancestral spirits.

be able to look at the unfamiliar and its relation to ourselves and to the world. These were objects from the Papuan Gulf, New Guinea, that the people of this region had associated with divinities living in the rainforest or on the sea, and with ancestral spirits.Surprisingly, the impressive catalog of the exhibition (2006, Hood Museum, Dartmouth College) made no mention the smiles on so many faces throughout the collection! And there was no suggestion that the people of the Papuan Gulf near Port Moresby have anything in common with ourselves. It reminds me of the unfortunate and oh, so wrong, way I once saw people in Samaná in the Dominican Republic when I first went to live with them, basically as different from myself.

In this lively figure, in its outward form and inner graphic lines, is there containment, but also something that corresponds to our own desire to be free? To be at rest and in motion at once? And to be pleased? In “Art as Humor," Eli Siegel writes that, “Humor in the long run is the seeing of reality as orderly and free, with the free predominating.”

Look at the face of this being. The cheeks are in motion. The brow lines press the eyes and the jawline closer together, while the cheeks swell out, as if impelled by the smile.

Look the eyes. Nothing is more contained than a dot, but in their darkness there is also something deep. They come forth and recede, and are related to the navel, which the Kerewa people consider the center of a being, through which it is joined to the world. The joints, which are inside the body, seem to be eyes. Is the unbounded in that? Then there are what might be legs. But they do not point down to the earth, but go into space, which has come into the figure.

The artists of the region agree that objects should have an axis of symmetry along the vertical grain of the wood. In this figure there are shifts towards the unsymmetrical. One shoulder is higher, with the head at a slight angle, giving the figure a somewhat more puzzled, critical look. Without these shifts the figure would be less. Mr. Siegel writes: “Humor can be seen too as reality with the symmetrical and unsymmetrical, and the unsymmetrical predominating.” What tendency this figure has toward the unsymmetrical makes this figure come to life.

The dignified black skullcap form at the top of the head is repeated upside down at the bottom, where the figure sits. Eli Siegel writes, “Humor is the feeling that the ugly is beautiful, while it is still seen as ugly first.” And he goes on to say, “Religion, to me, is essentially humor; for religion is a way of actually, factually, loving the real even though the real is seen as ugly, too. . . . The purpose of religion is to present the infinite in a finite, that is, a 'lesser' or 'meaner' form.”

This sculptural figure, so immediate and lively, does have a meaning that goes beyond it, that is very much represented in the smile. It is a religious object, an agiba, or skull hook. According to the catalog of the exhibition , it has a central place in the family shrines of the Kerewa people, which belong to the men’s mysteries and have their location in the men’s house. It has a relation to warfare. Starting in the 1900’s, the colonial government‘s ban on intertribal fighting and the arrival of missionaries had already made for great changes in the life of the people, and by the end of World War II people had abandoned their traditional practices. But the human questions that this object speaks to go on in them and in us.

The form that warfare took among these New Guinea people was the blood feud, where one tribe would retaliate against a neighbor for the loss of its members in a preceding raid, a cycle that endlessly repeated itself. At this time the agiba and more powerful religious objects, the spirit boards, would be brought together to unite the community and prepare it for war. After the community had exacted vengeance, the agiba would hold the enemy skulls together with the skulls of the ancestors. It is moving that these skulls are seen as belonging together, not as fighting, as of one another.

We know this region welcomed the missionaries and new forms of religious expression. So it seems that the smile on the face of the agiba represents a good hope in people. Dr. Perey has related this smile to the designs on the arrows that he brought home from New Guinea, that Eli Siegel said represented the hope to have a beautiful anger, one with like of the world in it.

I can use the agiba to ask myself, what kind of hope I want to have. I think the answer comes back in a way that has largeness and beauty, and also humor.

The artists of the region agree that objects should have an axis of symmetry along the vertical grain of the wood. In this figure there are shifts towards the unsymmetrical. One shoulder is higher, with the head at a slight angle, giving the figure a somewhat more puzzled, critical look. Without these shifts the figure would be less. Mr. Siegel writes: “Humor can be seen too as reality with the symmetrical and unsymmetrical, and the unsymmetrical predominating.” What tendency this figure has toward the unsymmetrical makes this figure come to life.

The dignified black skullcap form at the top of the head is repeated upside down at the bottom, where the figure sits. Eli Siegel writes, “Humor is the feeling that the ugly is beautiful, while it is still seen as ugly first.” And he goes on to say, “Religion, to me, is essentially humor; for religion is a way of actually, factually, loving the real even though the real is seen as ugly, too. . . . The purpose of religion is to present the infinite in a finite, that is, a 'lesser' or 'meaner' form.”

This sculptural figure, so immediate and lively, does have a meaning that goes beyond it, that is very much represented in the smile. It is a religious object, an agiba, or skull hook. According to the catalog of the exhibition , it has a central place in the family shrines of the Kerewa people, which belong to the men’s mysteries and have their location in the men’s house. It has a relation to warfare. Starting in the 1900’s, the colonial government‘s ban on intertribal fighting and the arrival of missionaries had already made for great changes in the life of the people, and by the end of World War II people had abandoned their traditional practices. But the human questions that this object speaks to go on in them and in us.

The form that warfare took among these New Guinea people was the blood feud, where one tribe would retaliate against a neighbor for the loss of its members in a preceding raid, a cycle that endlessly repeated itself. At this time the agiba and more powerful religious objects, the spirit boards, would be brought together to unite the community and prepare it for war. After the community had exacted vengeance, the agiba would hold the enemy skulls together with the skulls of the ancestors. It is moving that these skulls are seen as belonging together, not as fighting, as of one another.

We know this region welcomed the missionaries and new forms of religious expression. So it seems that the smile on the face of the agiba represents a good hope in people. Dr. Perey has related this smile to the designs on the arrows that he brought home from New Guinea, that Eli Siegel said represented the hope to have a beautiful anger, one with like of the world in it.

I can use the agiba to ask myself, what kind of hope I want to have. I think the answer comes back in a way that has largeness and beauty, and also humor.