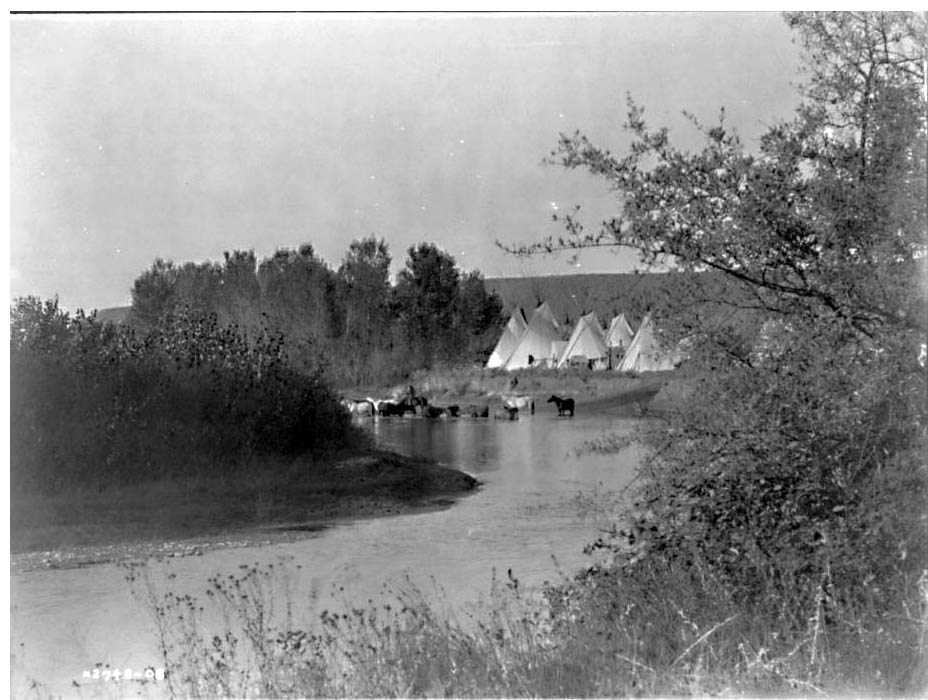

This photo from the early 1900s was taken by Edward Curtis on the banks of the Little Big Horn river south of Billings, Montana, on the reservation of the Crow nation.

In the middle distance are the horses on which the Crow men prided themselves and the white tipis that are present as abstractions in the art of the Crow women. Where once they roamed over a vast area, the Crow, who are also known as the Apsáalooke and the Apsaroke, are now confined to a 3600 square mile reservation. After Edward Curtis, they were visited by the great Boasian anthropologist Robert Lowie, whose work we have taken up in other classes. This paper is about the visual art of the Crow and the different ways Crow men and Crow women meet the world.

This photo from the early 1900s was taken by Edward Curtis on the banks of the Little Big Horn river south of Billings, Montana, on the reservation of the Crow nation.

In the middle distance are the horses on which the Crow men prided themselves and the white tipis that are present as abstractions in the art of the Crow women. Where once they roamed over a vast area, the Crow, who are also known as the Apsáalooke and the Apsaroke, are now confined to a 3600 square mile reservation. After Edward Curtis, they were visited by the great Boasian anthropologist Robert Lowie, whose work we have taken up in other classes. This paper is about the visual art of the Crow and the different ways Crow men and Crow women meet the world.The Crow economy was based on the roaming buffalo herds, and men and women worked together closely when they needed to break camp and move to another location. However, for the rest of the time Crow men and women had to work apart, the men to hunt buffalo and other game and battle the unfriendly bands of Dakota Sioux, Blackfoot, and Cheyenne, and the women to rear children, gather roots and berries, trade for the things they needed, and care for the horses.

Problems in the way Crow men and women saw difference, and each other, are told of in the legends passed down from one Crow generation to the next. There is a vivid story, “The Woman Who Married Worms-in-His-Face,” that describes the trouble a woman gets into when she feels that no man in her community is good enough for her and marries a stranger. I think this story is critical of the desire in a woman to stop thinking about a man and to have contempt for him. After a long series of perilous adventures, she manages to return home, but with a child, a supernatural being, that puts her people in danger. She needs to warn them about the child, but she keeps forgetting. A mouse asks her to put a feather in her hair so she will remember. And when she does, she is able at last to return to the community where she belongs.

are opposites that Crow men and Crow women put together in different ways.

In Is Beauty the Making One of Opposites, Eli Siegel asks: DOES every successful example of visual art have a oneness of outward line and interior mass and color? — does the harmony of line and color in a painting show a oneness of arrest and overflow, containing and contained, without and within?

In Is Beauty the Making One of Opposites, Eli Siegel asks: DOES every successful example of visual art have a oneness of outward line and interior mass and color? — does the harmony of line and color in a painting show a oneness of arrest and overflow, containing and contained, without and within? If you visit the current exhibition, “Infinity of Nations," at the Museum of the American Indian in downtown Manhattan, you will come upon a stunning display that includes four objects created by Crow men and Crow women that all celebrate the valor of the Crow warrior in battle, but do it differently. Of the Crow warrior psychology, Robert Lowie has written: “It is a queer blend of cruelty, vanity, greed, foolhardiness, literalism, and magnificent courage.”

The beaded objects for which the Crow are celebrated are the work of the Crow women. There's no denying that the ceremonial lance scabbard in gorgeous color, above left, has thrust from the use of the triangular forms and expansiveness from the use of the fringes. However, simultaneously, there is a containment through the geometry that is not felt in the same way in the men's works nearby. The beading on this scabbard case skillfully relates complementary colors, blue and yellow, red and green. Up close the beading is dazzling, yet there is an overall modesty, a subtle arrangement of the design elements that is very pleasing. Crow women restricted themselves to a certain limited number of traditional designs that they rearranged in imaginative

ways. The makers of this scabbard may have wanted to suggest the body and head of a horse and its flowing mane, and in the white triangles along the handle, the white tipis along the banks of the Little Big Horn. As the women worked, was it a way of keeping in mind the distant men who would carry a lance into battle? In the beauty of the design, were they expressing a good hope, perhaps, that their men would not have to fight? According to Aesthetic Realism, the care they showed expresses a desire that the men be ethical and fair.

ways. The makers of this scabbard may have wanted to suggest the body and head of a horse and its flowing mane, and in the white triangles along the handle, the white tipis along the banks of the Little Big Horn. As the women worked, was it a way of keeping in mind the distant men who would carry a lance into battle? In the beauty of the design, were they expressing a good hope, perhaps, that their men would not have to fight? According to Aesthetic Realism, the care they showed expresses a desire that the men be ethical and fair. The work of the men, while including contained forms, emphasizes individuality, daring, and expansiveness. There is the use of organic forms, both animal and human. The tomahawk at the right is the work of White Swan, a Crow warrior who became a Scout for the US Army and was wounded at the Battle of Little Big Horn. The design came to White Swan in a vision. The thrusting head of the tomahawk is a delicately carved swan in lustrous metal that shines out beyond its borders.

The work of the men, while including contained forms, emphasizes individuality, daring, and expansiveness. There is the use of organic forms, both animal and human. The tomahawk at the right is the work of White Swan, a Crow warrior who became a Scout for the US Army and was wounded at the Battle of Little Big Horn. The design came to White Swan in a vision. The thrusting head of the tomahawk is a delicately carved swan in lustrous metal that shines out beyond its borders.Another amazing work, the shield of Chief Arapoosh (Rotten Belly, 1795-1834), is also the espression of a vision. The design starts in two dimensions, from a center that is also the navel of a human figure, and expands in all directions. A medicine bundle and an eagle feather move it from flatness into depth.

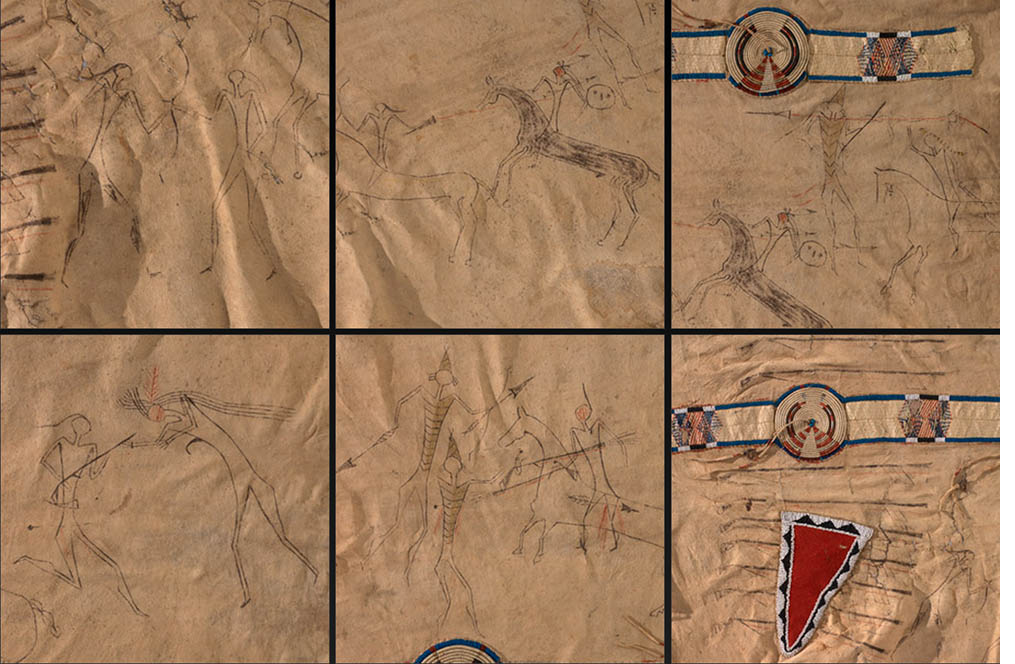

does what men and women are hoping to do in their lives. A highlight of the exhibition is a warrior’s exploits robe that tells a story: “I took a gun. I took a bow. I was wounded by the enemy. I killed one. I brought back eleven guns.” The drawings, the work of a Crow warrior, are expansive, filled with activity and motion. Meanwhile there is a lovely, tender feeling in the way the horses are drawn.

At left is a series of closeups from the full robe, which is made from a buffalo hide. In the full robe a long rectangular strip with beaded rosettes made by the Crow women runs down the center. It is the geometry of that strip we see first, and the containing outline, but the beading and the ribbon have a luminosity that is unconfined. The red triangle, its saw-tooth edge black and white containing a patch of fiery color, represents a horse’s head. The saw-tooth edge contributes to a feeling of energy radiating out from a center, which is otherwise not so common in the women’s work, and there are the delicate loops coming from the centers of the rosettes that do the same thing. We feel a coherence between the buffalo hide with its drawn figures and way the women have embellished it. In this work Crow men and women meet respectfully, as they are hoping to do in their lives.

At left is a series of closeups from the full robe, which is made from a buffalo hide. In the full robe a long rectangular strip with beaded rosettes made by the Crow women runs down the center. It is the geometry of that strip we see first, and the containing outline, but the beading and the ribbon have a luminosity that is unconfined. The red triangle, its saw-tooth edge black and white containing a patch of fiery color, represents a horse’s head. The saw-tooth edge contributes to a feeling of energy radiating out from a center, which is otherwise not so common in the women’s work, and there are the delicate loops coming from the centers of the rosettes that do the same thing. We feel a coherence between the buffalo hide with its drawn figures and way the women have embellished it. In this work Crow men and women meet respectfully, as they are hoping to do in their lives.I hope the men and women of the modern Crow nation will soon meet the explanation of beauty, Aesthetic Realism, that I am proud to be studying in this class with Dr. Arnold Perey, based on the kind and powerful principle stated by Eli Siegel: “All beauty is a making one of opposites, and the making one of opposites is what we are going after in ourselves.”