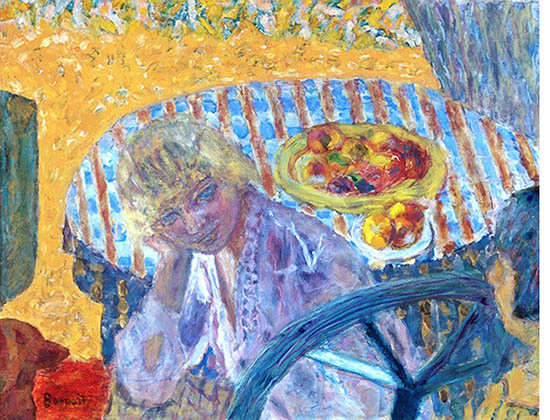

“Young Women in the Garden” is a painting that Bonnard began in the early 1920s but did not complete for more than 20 years. Renee Monchaty, who died as a young woman, sits in a deep shadow, facing us, with a light falling on her hair and right shoulder. She looks at us as Bonnard’s wife Marthe, from the right side of the painting, looks at her. A garden chair rising from the bottom of the painting comes between the two women, but also joins them.

“Young Women in the Garden” is a painting that Bonnard began in the early 1920s but did not complete for more than 20 years. Renee Monchaty, who died as a young woman, sits in a deep shadow, facing us, with a light falling on her hair and right shoulder. She looks at us as Bonnard’s wife Marthe, from the right side of the painting, looks at her. A garden chair rising from the bottom of the painting comes between the two women, but also joins them.Half hidden in the lower left corner, a dog, a little critic, completes the triangle of figures, a triangle that is between two curves. A sunny background in saffron yellow, drenched with petals, comes forth as the shadowy foreground recedes, giving the composition the flat feeling of a fourteenth-century religious painting. Within this flatness is a stir of opposing lines and color that wants to burst its bounds.

In Is Beauty the Making One of Opposites? Eli Siegel asks this about outline and color:

Does every successful example of visual art have a oneness of outward line and interior mass and color? — does the harmony of line and color in a painting show a oneness of arrest and overflow, containing and contained, without and within?

The line of the table is steeply raked and the fruits, the brightest objects in the painting, look ready to jump out of their bowls or roll down the table, they are so fresh. Bonnard loosely indicates their planes with bright spots of paint, and then with a disregard for outer form, again through color, dives into their depths.

A Frenchwoman at the Museum, watching as I studied the painting, exclaimed “But how could he have painted that in wartime. We had no fruit then. It all went to Germany!” A few minutes she came back. “Ah, Bonnard painted from memory!”

as I studied the painting, exclaimed “But how could he have painted that in wartime. We had no fruit then. It all went to Germany!” A few minutes she came back. “Ah, Bonnard painted from memory!”

It is a memory picture. The figure of Renee is worked and reworked, tremblingly iridescent. Bonnard was trying to see. Meanwhile the fruits could have been painted yesterday.

In life, Marthe was jealous of Renee, and Bonnard had to wait until after her death to complete this painting. What restriction and abandon are in that drama! Meanwhile, every stroke of this painting is against competition and for meaning. Renee is in a dazzling lavender robe that we see includes the darks that are in Marthe’s hair. Marthe’s dress has the color and pattern that are in Renee's hair. Does each woman add to the other’s meaning the way profile and full face are aspects of one person, the way being both critical and being pleased can be?

It is my good fortune to be learning in Aesthetic Realism consultations and in the great Visual Arts class taught by Marcia Rackow that the answer indeed is yes.

as I studied the painting, exclaimed “But how could he have painted that in wartime. We had no fruit then. It all went to Germany!” A few minutes she came back. “Ah, Bonnard painted from memory!”

as I studied the painting, exclaimed “But how could he have painted that in wartime. We had no fruit then. It all went to Germany!” A few minutes she came back. “Ah, Bonnard painted from memory!”It is a memory picture. The figure of Renee is worked and reworked, tremblingly iridescent. Bonnard was trying to see. Meanwhile the fruits could have been painted yesterday.

In life, Marthe was jealous of Renee, and Bonnard had to wait until after her death to complete this painting. What restriction and abandon are in that drama! Meanwhile, every stroke of this painting is against competition and for meaning. Renee is in a dazzling lavender robe that we see includes the darks that are in Marthe’s hair. Marthe’s dress has the color and pattern that are in Renee's hair. Does each woman add to the other’s meaning the way profile and full face are aspects of one person, the way being both critical and being pleased can be?

It is my good fortune to be learning in Aesthetic Realism consultations and in the great Visual Arts class taught by Marcia Rackow that the answer indeed is yes.